The Marion Lynching Trials

Contents

Overview

When Tom Shipp and Abe Smith were lynched, the African American community and its supporters demanded justice. Unfortunately, no one was ever held accountable for these gruesome deaths and no conviction was ever made regarding the Marion lynching. The entire judicial system was manipulated by members of the mob and government officials who wanted to get reelected next term and could not afford to lose the votes of white citizens in Grant County. A web of lies and deceit was uncovered as those who demanded justice could not find any support nor could they find anyone courageous enough to stand up against the massive corruption that had Marion and all of Indiana by the throat.

Flossie Bailey and the NAACP's Fight for Justice

Katherine Bailey, or Flossie as she was more commonly known as, was a local African American woman who expertly developed and led the Marion branch of the NAACP. After the immediate threat of more racial violence ensuing passed, Bailey turned her focus towards bringing the leaders of the lynching mob to justice. Her first course of action was to call L.O. Chasey, the governor’s secretary in an attempt to receive support from the state government. This failed miserably as he hung up on her, signaling that receiving support from the state would prove to be difficult. Chasey was from Marion and was close friends with the local authorities there. One Republican told the governor Chasey “has too many Grant County connections and political friendships in the mob” (Marion Chronicle, August 14, 21, 22, 1930). She called for the assistance of the head of the NAACP. The organization responded by sending one of its leaders and hiring a private investigator (Grant, 149-160). The investigators concluded that the Marion police officers did not do an adequate job in preserving the peace and stopping the mob. The NAACP called for the removal of Jake Campbell as the town’s sheriff. It was also believed that the town would be cursed with being associated with this event until the murderers were brought to justice. Obviously this was not going to be possible because all of the local government officials claimed that if they did anything to bring these people to justice it would revive the mob leading to more violence, an excuse offered much too often by government officials. Flossie Bailey met with several other NAACP leaders and went to see Governor Leslie. Their goal was to convince the governor to strip Jake Campbell of his status as sheriff and to encourage the prosecution of the mob leaders. Leslie was unresponsive and offered no support.

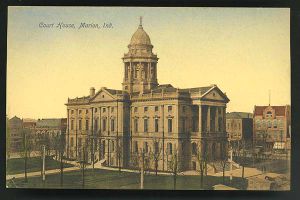

Court of Inquiry

On August 13, 1930, the Court of Inquiry opened and called 30 witnesses (Lynching Depositions). Throughout the three days the of proceedings the county prosecutor, Mr. Harley F. Hardin, pressed many police officers and citizens in pursuit of some form of evidence that might be useful in finding out the identities of the leaders of the mob. Nearly everyone said that they did not recognize anyone they knew in the mob. With everyone having the same story it became increasingly obvious that the entire community was content to withhold the identities of the mob leaders. They did this either out of fear of being punished by members of the mob for revealing information or because it was unanimously decided that they did not want anyone to be punished for the murders of Tom Shipp and Abe Smith. It is possible that the white community wanted to further divide the white and black populations in Marion. Throughout the proceedings Shipp, Smith, and Cameron were constantly referred to by some racist label. Either they were called “negroes” “colored men” or even “niggers” (Madison, 80).

Roy Collins

Roy Collins, the assistant chief of police, was the first in a long line of witnesses. He was questioned many times for any information that could lead to establishing the identities of the mob leaders.

Q: Were the lights sufficiently strong there for you to have distinguished and recognized the features of any one?

A: I don’t believe they were, if they were I didn’t see them; I am telling you the fact, I couldn’t tell you a soul that was there. I saw their faces there and if I would see them again I would know them in a minute, but I didn’t know them.

He was then asked if specific people, who were suspected of being the mob leaders, were in the mob in order to narrow it down for Collins.

Q: Do you know Charles Lennon when you see him?

A: Yes sir, I know him when I see him.

Q: Did you see him there that evening?

A: I did not.

Q: Do you know Asa Davis when you see him?

A: There are two Asa Davis’s in town.

Q: The musician?

A: I know him when I see him.

Q: Did you see him there?

A: I did not.

(Lynching Depositions, 4)

He was then asked if he had talked to anyone who claimed to know of anyone in the mob. He answered that he had talked to several people, John Fryer in particular but Fryer did not tell him what the name was or who he heard it from. Hardin asked Collins a final time if he could remember anyone in the crowd and Collins responded with “I couldn’t describe nobody, it looked to me like a whirling mass of humanity, that is all I can tell you.” (Lynching Depositions, 4)

Chester Marley

Hardin asked Chester Marley, a local patrolman, if he saw anyone. He failed to get any information from him as well and asked if all the members of the mob around the jail were strangers to Marion. Marley replied saying “I didn’t see a fellow I knew” (Lynching Depositions, 133). John Fryer, the president of the city planning commission remarked that “I never saw so many strange people around here in my life” (Lynching Depositions, 143)

Samuel Wycoff

Samuel Wycoff, an average citizen, was asked if he knew anything about the planning of the lynching. While he did not know anything he did remember an interesting encounter.

Q: During that day, did you learn anything about any rumor or talk about a lynching party?

A: I didn’t, all I know is, I went to get in my car over here and some fellow holloa’d and said “where are you going” he didn’t even call my name. I said “ I am going home” He said “You better come back” or something like that “there will be something doing” That’s all that was said, he didn’t say what it was.

Q: Do you know who that was?

A: No sir; there was just a bunch standing over here on the corner where my car was parked.

Q: Nobody came to your home that day?

A: No sir; I am not sure.

Q: And said anything to you about the lynching?

A: Not a word, in no shape or form, they know where I stand on such things; I suppose the reason why he holla’d at me, I used to belong to the Ku Klux; everybody knew it, of course, he might have thought I was hooked up in something of that kind, but I never approved of such things in my life.

Q: You don’t believe in lynching?

A: No sir I do not.

(Lynching Depositions, 158-159)

Wycoff went on to say that the only one he heard talk about the lynching was John Pittenger, a retired mail man. Hardin asked him if Pittenger recognized anyone that was around the crowd at the time of the lynching and he said “No sir. I believe he did say, he didn’t know any of them, they was all strangers to him, that is the remark he made; he said I didn’t know any of them they were all strangers to me, is what he said I think that is the remark he made.” (Lynching Depositions, 160)

Conclusion

It was obvious after all 30 witnesses were called that evidence was basically non-existent. Attorney General Odgen indicted seven Marion residents he believed to be the mob leaders but not one of them was convicted. The white community suppressed any information that might lead to the identities of the mob leaders and offered no support when questioned. When the cases were going to trial everyone knew that the chances of a conviction were slim. Flossie Bailey believed that they would have their self-respect if they at least tried. She gathered many members of the black community and on the last day of the trial against Lennon, a suspected leader of the mob, 20 African Americans sat in a courtroom filled with hundreds of whites in a courageous and silent stand against racial violence. (Southern Commission on the Study of Lynching, 55) Throughout the entire incident Flossie was determined to see justice done, even when no one else was. Not only did racial violence break out on August 7,1930, but Lady Justice, herself, was slaughtered that night and her presence in Marion, Indiana was practically non-existent through the events that followed.

Work Cited

Marion Chronicle, August 14,21,22, 1930.

Donald L. Grant, The Anti-Lynching Movement, 1883-1932 (San Francisco, 1975).

Court of Inquiry, Lynching Depositions, August 13-15, 1930.

James H. Madison, A Lynching in the Heartland, Race and Memory in America (New York, 2003).

Southern Commission on the Study of Lynching, Lynchings and What They Mean (Atlanta, 1931).

Credits

This article was written by Brandon L. Houser for Mr. Munn's ACP U.S. History class, second semester project.